Well, it’s not really the plumbing that needs to stay healthy, but rather the people who use the plumbing. It’s not a bad idea to keep the plumbing in good shape too. To me, healthy plumbing is a system that delivers enough water at the temperature you want, whether hot cold. It delivers clean water, without bacteria, viruses, metals, sand, or other stuff. It delivers hot water fast, without much energy or water waste, and gives you cold water quickly as well. The piping system shouldn’t cause other problems, like expansion noise in the walls, or velocity sounds. It’s good if it doesn’t sweat, dripping water down onto sheetrock ceilings. It should be installed so it is safe from rodents and does not give them passageways to travel around the structure of the home. So, let’s have a look at this list and see what to keep in mind: Having enough water. This is a function of pressure and the sort of fixtures you have. Normally, pressures between 40 and 60 psi are what we want. Anything much lower can cause insufficient flow and too high can stress the plumbing system, or make water hammer a problem. Check pressure with a gauge that screws onto a hose bibb. I like to use a 0-200 psi gauge, and measure when no water is being used. It’s not much fun when you’re in the shower and somebody flushing a toilet causes the temperature to change quickly! Using “pressure compensating” showerheads and aerators will go a long way towards keeping flow the same, even with varying water pressures. Pipe size matters too. If the pipe is too small or became too small by filling up with rust or scale, you won’t get adequate flow. Generally however, codes have made us put in pipes that are far too big for the ever-reducing flows we have in our homes. We used to have much higher water use fixtures than we do now, so flow rates continue to drop, but plumbing code hasn’t kept up. At present, they’re about sixty years behind reality. The right temperature. This is a tricky one as hot water temperatures that are comfortable for people are also good for growing bugs like legionella in the plumbing. Temperatures that kill off the bugs will scald people pretty fast. For people not too old or young, and in good health, 130 degrees F is usually a good place to set the heater to, as it doesn’t promote bacterial growth and doesn’t burn people that quickly. Modern, pressure balanced shower valves are absolutely worth putting in as they help prevent rapid temperature changes in the shower. Another approach that’s becoming common is to install a tempering valve downstream of the heater, so you mix down hotter water to a safe 120 degrees or so. Even this approach could let bugs grow in the piping, however. As I said, this is a tricky problem! Having cold water stay cold and not sweat and drip condensation is a concern for humid areas. It may seem counterintuitive, but insulating the cold lines is a good way to prevent problems here. Pretty simple! Of course, all the hot lines should be insulated too. Clean water. This one matters! Think of Flint, Michigan. We don’t want bugs, metals, chemicals, or other bad things in our drinking water. Pipes that are too big, or have unused portions called “dead legs” in them are the perfect breeding grounds for nasty bugs. Sizing the pipes so you get at least one foot per second of water flow through them helps scour the pipes, preventing bugs from having a place to hang out. This flow also keeps sediment from being able to settle in the lines so much. About metals, we need water that is not corrosive to the piping material, and we need materials that don’t contribute to the problem. With older faucets, it’s common to have way too much lead in the first flush of water in the morning. Particularly if the water is acidic or over-softened. Older faucets had lead in them to make machining the brass easier. We’ve learned a little since then! Lead was often used in the supply system to connect branch lines because it could flex. There are better ways to fix that problem now. Debris can simply be flakes of rust from steel piping or silt from wells, or other stuff. Fortunately, it’s not hard to filter this gunk out, but be sure to keep the filter clean and out of the sun or it could become another source of bugs and algae! Energy and water waste. This one gets taken care of with good piping layout and sizing. Recirculation lines that run 24 hours can triple your water heating bill… and they damage piping. The basic idea is to put in pipes that are only big enough to give you enough water and no bigger. They should be kept as short as can be done. This all creates low volume plumbing, so less water must be flushed out to get hot or cold water. Interestingly, if you have a gallon in the lines between the heater and tap, you’ll have to waste between one and a half, to two and a half gallons before getting hot water. That can be a significant waste of water, energy, and your time! So, see if the water heater can be put close to the fixtures to shorten the piping runs and then keep the pipes as small as you can. Other problems. I’ve covered sweating pipes, but not touched any rodents! Plumbers sometimes seem to enjoy drilling rather large holes in the framing to run their pipes through. The mice like this! It gives them easy access from crawl space to attic. Sometimes you can hear them behind your headboard at night, partying! Rodents don’t use toilets, so things get a bit unsanitary. The hantavirus is not something you want the critters to give to you. Rats are smart. They know water is in those lines. If you’re using plastic lines, like PEX, that rat just might chew through the line to get a drink. I’ve seen it happen and it’s not something you’ll discover right away. The wood framing that’s getting sprayed could rot and need to be replaced and then there is that big water bill. This problem can be avoided by running small plastic lines in bigger conduit, when going through crawl spaces or other places rodents can’t readily be kept from. It’s a bit of a pain to do, but far easier than dealing with the problems that come of not taking that precaution. Expansion, water hammer, and velocity sounds are the last things I’d like to touch on. Metals expand a little when heated and plastics expand a lot more. When installing copper pipe, it’s good to use plastic bushings when going through wood, so there is a way for the pipe to move quietly, rather than rubbing hard on the wood and making creaking or popping sounds. Soft plastics like PEX can be installed so that they can bow out a bit when heated by the hot water inside. PEX tube expands and contracts one and one tenths of an inch per 100 feet, per 10 degrees F change in temperature. So, if it goes from 50F in your crawlspace to 130F with hot water, that’s an expansion of 8.8 inches per 100 feet. Where’s that extra pipe gonna go? It’s a good thing for the plumber to keep in mind. Velocity noise happens when water is moving too fast through the lines or fixtures. This could be the result of a reduction in size caused by corrosion where different metals meet. For example, where copper and steel meet, the steel rusts, reducing the path for water flow. Valves may get hard water build-up inside and hiss when running water. Good clean water, good piping design, pressure control, and pipe sizing will go a long ways towards quieting these things down. Water hammer is what happens when water is moving fast down the line and is made to stop quickly, by closing a valve too fast. It’s more of a problem with the combination of too high a pressure combined with fast closing automatic valves, like you find in washing machines or dishwashers. If simply controlling water pressure doesn’t fix it, then water hammer arresters can be put just in front of the valves that are causing the problem, and that gives a cushion for the water to hit, rather than a brick wall, as the valve closes. I’ve only touched briefly on some of these things… a book could be written, but hopefully you see how each part affects other parts of the system. The human component is the most variable one, and sometimes doesn’t obey the laws of physics like the rest of the system does, but we adapt 😉 Yours, Larry

0 Comments

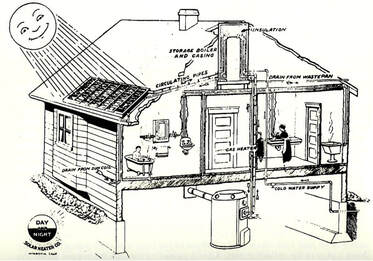

Although I don’t go as far back with solar water heating as Day and Night Solar, I am one of the old guys in the field having built my first system in 1978. I installed new solar right up to the end of tax credits in 1986. Then 90% of the solar companies in my area vanished and I took on keeping all those local orphan systems running. What I saw taught me a lot about how not to do solar. People had installed copper coils in galvanized tanks. This caused the tanks to leak within a year or two. Some installed the solar tank downstream of the electric “backup” tank, so electric was heating the solar tanks. Just imagine that meter spinning! Drainback systems were put in so they couldn’t really drain back, and pipes froze. The wrong insulation was used and would melt off the pipes, or no insulation was used at all, or was sloppily installed, so it didn’t really work. Pumps would come on during freezing weather, so pipes that would have been fine, burst because of controls poorly set up……… I saw systems so complex that it took a longish time to figure out what the installer might have had in mind. Systems like these reminded me of being inside of an older style diesel submarine with pipes running everywhere. Perhaps the installers were proud of these systems because it was common that they had no insulation… probably to show off all the shiny copper piping! If you’re going to have a system like that, you need to build a separate bedroom for the installer as he or she will be spending a LOT of time at your place. At least put a cot in the mechanical room! So, I got to learn a few things. First is Elegant Simplicity. This matters because the more complex something is, the more ways it has to misbehave. Just think of the interactions between parts. If there were only two parts, that’s two interaction. Three parts means six interactions. Four parts means twelve interactions, and so on. Keeping things simple, by actually putting the properties of the materials to use, is a great way to build a durable system. The only problem is that it requires thoughtful design. I had the pleasure of working with Steve Baer, of Zomeworks in New Mexico. He was a champion for the practical application of elegant simplicity, and he wrote a lot of good things too. The book: “Sunspots” is likely his best-known work. If you want durable and efficient systems, elegant simplicity is THE way to go. It’s also useful to study the history of solar, so that you understand the ideas that have come before. See if you can find a copy of “A Golden Thread: 2500 Years of Solar Architecture and Technology”. It’s a fun and useful read! It also makes sense to design systems that are a good match for the people living there. A very complex system might be fine for the plumber or engineer who likes to tinker, but not so good for the busy professional who works primarily with their mind, rather than their hands. I learned that most people ignore maintenance, so it becomes important to design systems that may only need to be seriously looked at about every five years. That’s hard to do. Also, they need to be designed to fail in a safe way, rather than failing so water leaks out or steam from stagnant collectors fills the garage! One of the most common systems around the world is the thermosyphon type. It places the storage tank above the collectors so warmed water flows by convection from the collectors up into the tank. Having no controls or pump to fail is simpler! Even so, that type of system doesn’t do well in cold climates, but there is no need to have only one system type to cover all areas. There might be places where photovoltaics should power a heat pump, just because any outdoor plumbing is risky. Leaving the past for a bit, I’ve more recently built systems that come pretty close to being simple and perform far better than conventional solar, along with costing about half as much. The key to doing this is to not look for the most efficient collector, but rather, an inefficient collector! By having more square feet of inefficient collector area, you get more BTUs and eliminate the risks and design challenges of overheating. By using the right type of plastic collector, you nearly eliminate the risk of freeze damage. Also, the collectors cost less and are even something that a handy person could make themselves. Add to this, using a well-insulated plastic storage tank and “too much” insulation on the lines allows this system to take care of 90% of the user’s hot water needs! Also, there is very little to maintain. Not bad! A normal “good” system can do 70 or 75% and many do far less. Throw in a little efficiency in the plumbing distribution and fixtures and you will be able to take long, luxurious showers and still be efficient! I’ve only skimmed over the topics of history, design, and efficiency. Still, I hope you understand now that solar thermal can be done well and cost effectively. It does not need to be relegated to the dust bin of history. But, it must be done thoughtfully to work well, long term. Yours, Larry |

Larry Weingarten

Looking back over my working life of 50+ years, it seems clear that self sufficiency has always been the best way for me to be useful. Now, mix in a strong interest in water in its many forms and the wide world of animals and you'll know what's important to me. Archives

January 2023

Categories |

Copyright © 2014 - 2023

All Rights Reserved

All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed